Excerpts transcribed from audiotape. Anthony did several demonstrations during his talk.

I've left out the parts where you need to watch what he's doing in order

to understand what he's saying.

[Square brackets] indicate either my paraphrase of parts of the tape that weren't clear

or explanatory notes or commentary to make the text more readable.

[laughter] indicates

laughter from the audience.

[?] indicates I don't have a clue what was said.

Ellipses indicate quotes dropped because they either weren't clear on the tape or they

were repetitious/redundant and don't add any new info.

All audience questions are paraphrased for brevity's sake and because many of them weren't

clear on my tape.

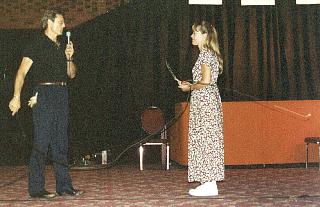

Anthony began by shanghai-ing the guest speaker before him — Battlestar Galactica's

Anne Lockhart (Sheba) — to help with his first demonstration:

Whenever I'm working with a beautiful actress, I always make sure that she trusts me. [in

evil voice] Do ya trust me?.... [starts cracking whip and keeps cracking whip as he talks]

This is a bullwhip, which is made out of kangeroo hide. It's a wonderful piece of work.

Each one is made by hand. I get these from Australia, where the whip

is still a working tool, just like it used to be in this country. The

Australians, they don't use ropes to herd their cattle; they use the

sound of a bullwhip. Who knows why the whip makes this sound? [audience

says something] Yes, it does [cracks whip] break the sound barrier.

The whip goes over 700 miles an hour. [grins at Anne Lockhart] Oh boy,

this is a good time to tell you I lost my medication. [laughter]

We've reassured her just a little bit. Now we're going to talk about some safety rules.

Anytime you're working with a partner, the first thing you do is signal

with your eyes. [to Anne] Are you ready? Good, she's ready.

Okay. Also, one of my safety rules with the whip is, the whip always works outside my

hand, as you can see, because if it's inside my hand, I'm going to be

[?]. The other thing is I think about... railroad tracks. So I stand

inside the railroad tracks, and the whip is outside the railroad tracks.

So ideally, anything inside the railroad tracks with me is also safe.

No matter how close I get, she is absolutely fine as long as she is

inside the railroad tracks with me.

[to Anne] Could you hold that feather for me in your left hand? Right about there....

So what I'm going to do is take that [feather] out of her hand, ideally

without hitting her hand. You should see the look she's giving me! [laughter]

Knocking the feather out of Anne's hand

[cracks whip and knocks feather out of Anne's hand] Lose the death grip. [laughter] But

if she leaves her hand out there, I would want to send [the whip] out

past her.... Instead of cutting down through her like the target. When

I'm working with a partner, I send it out past her... so it's very soft

and gentle. [The whip curls around Anne's arm then slides off.] If I

want to wrap it around [her] legs, like in Hollywood sometimes [the

hero] sees someone he likes and wants to catch her. [The whip curls

around Anne's waist. She spins towards Anthony and into his arms. Loud

applause and cheers.]

As you noticed with the whip, we talked about... a few safety rules, the idea being, well,

first of all, I want to keep myself safe — I don't want to hit

myself because something that travels at the speed of sound hurts.

A lot. Also, because the tip [of the bullwhip] is going over 700 miles

an hour, that's a tremendous amount of responsibility if you're working

with a person. So you never want to work beyond your level of ability.

I've been doing this for about 15 years now and I get [?] every once in a while. I...

train people. I trained... Catwoman [Michelle Pfeiffer in Batman

Returns]. I got a call doing... Madeline Stoke, the lady [that]

she is, didn't listen to me.... She put me on the spot because she was

supposed to slowly turn and walk to the door and she [storms off quickly].

I'm going like Damn! [cracks whip] I had to wrap that around

her neck without her getting out the door and also without making any

marks. It worked out, so you didn't need to read about anything in the

newspapers. It was a successful day.

Being an actor, a storyteller, problem solver, I'm in the business of creating illusion.

Sometimes when you're working with something like this, you've raised

the level of the risk factor, so you have to be very very cautious with

your illusion. But at the same time, there are a great many things you

can [do with this].

I studied fencing for over 20 years because it's my hobby. I have a great love of this

kind of weapon.

This [the bullwhip], I taught myself, because I thought it was the most theatrical thing

I'd ever seen, and I couldn't afford to have somebody teach me. So I

got a whip, and we spent a little time together, and slowly but surely

she started to reveal her secrets to me. And you ask why it's a she?

She saved my life a few times.

But more than anything else, this taught me to put together all the pieces of all the things

I've learned. I've had two really great teachers in my life. One was

Mr. [Rob Faulkner?] of [Faulkner] Studios in Hollywood, a grand old

man of fencing. He was an Olympian in 1928 and 1932, I believe. I studied

with him for over a dozen years. He did things like... Prisoner of

Zenda.... and many many other of your favorite action films. I learned

a great deal from him.

I'd absorbed a lot of information, and hadn't quite put all the pieces together, and this

[the bullwhip] really did it for me.... The idea being that this has

no life at all; it's a dead thing. But because of it's very structure

— this is the first man-made tool to break the sound barrier —

I don't need a lot of energy. I don't have to really whip that thing

around and put a lot of energy into it. I can get this to do the work

for me. This gives me literally fingertip control. Notice how soft my

hand is.... What I'm utilizing is the line of my body and the actual

structure of the whip.

What makes this work is you have the broad handle that tapers continuously all the way

down through the body of the whip, which is a whip inside a whip actually

— it's a braided core wrapped in leather in an outer braiding.

Well, the spiral braid allows it to compress and expand.... A tremendous

amount of energy is exchanged during the course of a crack of a whip

[and it unfolds all the way down to the cracker at the end]. It's called

the acceleration of kinetic energy. That's why it makes the noise.

Water flows downhill. So if I utilize the alignment of the whip itself.... it becomes a drag

[then] a push to get the whip in front of me so I don't have to worry

about getting hit. Notice how my body moves out of the way, and my entire

body points where I want the whip to go.

Also with this, because I want to use my whole body, because I'm telling a story, I

want to start with my feet so that I have a base for my entire body

to tell the story. This taught me how to do it, and I had an awful lot

of fun with it.

| To top |

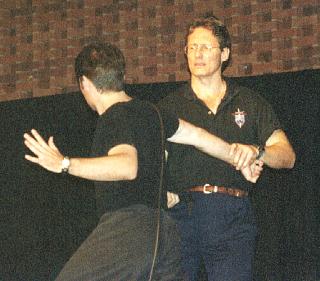

Demonstrating a fistfight

This is my [fighting partner], Simon Fon.

When you [have a fight scene] as an actor, it's just like when you're doing a role. The

first thing you look at is the script: What are the clues that the author

has given you around which to build your character? What's said about

him, and from that, what can you infer?... You get inspiration, then

you bring your own interpretation of those things and slowly but surely

through a series of choices, your character is articulated.

What I like about action is that it's exactly the same; it's just very visual and dynamic.

So something like this [the whip], I've got the long distance to reach out and crack.

Now again, safety wise, the first thing I do is make sure that I'm out

of range. Simon knows I can't hit him which he feels much better

about it. [laughter] Now if I bring this across like this [cracks whip],

and he fakes that reaction, you're going to be absolutely sure that

I smacked him, with the camera behind him.

So he's out of range, and I'm sure he's out of range before I ever let this go. You want to

create an atomosphere of safety to work in because then you can be creative.

But in addition to that, I also have some other things working for me.

Everything you do as a part of a scene is dialogue. If he says something, I react to it.

Even if I seem not to react to it, that is a reaction. That is a choice.

The story is told by what you choose to do. When I'm working with a

partner... we have a dialogue with the body too.

We talked a little bit yesterday about how imporant it is to prepare yourself because you

have [little] time, especially if you're working [in] television. In

eight days you shoot what feature film gets three weeks to shoot. You

have to prepare yourself. You have to have done your rehearsal before

you show up that day. You [already] have the skill you have cultivated

the day you walk on the set.

Now what's important about this is skill... [it] gives you experience and it makes you recognize

opportunities. It lets you make opportunities... and choices. Just like

with an actor where you choose what the scene is about, what story am

I trying to tell, and what would this character do — all those

imaginative ideas — the same thing happens with a physical scene.

What [Simon] does and how I respond to it is the story that we're going

to tell you.

A lot of actors, unfortunately, are in a hurry to get the job done as opposed to savoring

the telling of the story. So when I throw this punch here like this,

there is a little piece of action there a moment before.. and I tell

you [through how my body moves] what's important to look at. There is

the action itself — boom! [throws punch ]. There's the reaction

[Simon jerking head back]. And there's the moment afterwards.

All of these are storytelling tools. You can be in a big hurry and get done and not too

much happens, or I can go Ugh! and react too.

What I like to do when I work with actors is talk about [?] .... So I will say if we do

this, we tell this story. If we do that, we tell that story. Which one

seems more like the character that you're building? We have the character

up to that moment in the story, we have the story of the action itself,

then we pick up the story [again] afterwards. We should utilize that

opportunity to move our story into something unique... and make you

guys respond.

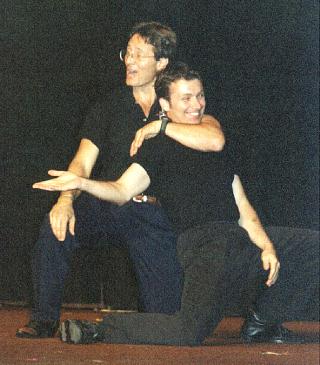

[There's] long range, speaking [i.e. taunting] range, punching range, and grappling range.

This exists with no weapons and all weapons — a variety of distances.

Each of those is a storytelling tool.

I also want to be aware of the camera, because if I'm aware of the camera, I can make

the [cameraman 's job easier]. When I make the cameraman's job easy,

then he will make me look good. So I always have a running dialogue

with the camera: Where are you? Is this good for you?

| To top |

Just a friendly headlock

When there's a weapon, it's more likely to go out of control.... So I will connect this [sword]

to my body.

Simon and I haven't worked out for a year, but we have our own system of parries. We use

six parries. [demonstrates] Now you notice, as he delivers his cuts,

he's not just smashing into me. He's controlling the cuts and he's telling

the story with [how he moves] his body as opposed to how hard he can

hit with the blade.

One of the nice things about The Three Muskateers is you had a real sense in

that that anything goes, that they would do anything to win and survive,

and that was a wonderful overlay to the whole thing.

Bob Anderson when he did The Princess Bride, he had six weeks to train Mandy Patinkin

[then the shooting started]. So basically he had about 12 weeks, which

is a wonderful luxury to develop your artist, to develop the skills

and vocabulary, and to put together a fight that highlights his experience

and really articulates his character. It's a rarity, but you can see

how wonderful it is when it works.

With Michelle Pfeiffer, I had six weeks to train her, so we developed a vocabulary where she

would literally walk in, choreograph then shoot it.

I can put together a fight in... well, maybe a half hour. Then we would rehearse and be

ready to shoot a couple hours later, but it's not the ideal way to work.

You're playing catch-up all the time. That's very difficult.

Oh, what I was going to say about The Princess Bride is, at no time were you ever

worried that anybody was going to get hurt. There was a wonderful overlay

of the kind of fun I had as a boy, which got me into swordfighting in

the first place. It was a whole story about two guys who were so enamored

of each other's technique and ability that they were out having fun.

So the audience had fun. And that's the story that they told. But underneath

it all, there was never any sense of danger, or that anybody was going

to get hurt.

| To top |

Duelling with sabers

Anthony did swordfight demonstrations where each opponent had a saber, each

had a saber and a dagger, each had two sabers, and where Simon had two

sabers and he had only one. Afterwards, he took questions from the audience:

When you're working with a fight scene, how much do you work with the cameraman

to block out angles? And is the finish product what you imagined?

What usually happens is a fight gets put together, and hopefully you get to work with the

artist prior to walking on the set, although I have been on shows where

literally myself and the other artist are shown the choreography for

the first time [when] we're blocking the action out before the shoot.

I hate working that way. I can... but I've done my homework. It's not

the best way to work because you always hold back a little bit because

you're not quite sure what the other guy's going to do. So you wait

to see.... Just about the time you're ready to really do the fight —

because hopefully I [now] know I can count on this guy; he's consistent;

he's safe; this is the story we're going to tell — we're done shooting.

In an ideal situation, you work with the artist. You then show it to the director and he decides,

"That's the story I want to tell" or "Uh... that's not

quite really what I wanted," so you make a quick fix hopefully,

and then you show it to the cameraman, and he directs the camera. Usually

he doesn't tell you about it other than to shoot it.

I personally like [?] because I can take advantage of that knowledge. But then I have

a whole other career behind the camera. Knowledge to me is power in

the sense that [I can] utilize that information to do a better performance.

To open myself to the camera.

As far as editing goes, it's very very rare that I get any input in that. Again, in an

ideal world, especially if I'm choreographing or directing — essentially

when I'm choreographing, I'm directing that scene. I am assembling the

characters; I am helping the director make those choices; then I'm helping

with the execution of those choices to tell the actions of the story.

All of the input and the creativity of the artist is involved.... No

two takes are ever quite the same, so you do get a little bit of the

excitement that you get in live theater.

But what always happens, particulary in television, is that it's shot and shipped back

to editors who may not know exactly what the director and the choreographer

and the artist had in mind. So they are left with having to make the

best choice they can make with little information.

A director will have a vision — you notice when you go to see a move, you look

at the film, the way the camera moves all the time. Quentin Tarantino

has a very definite style. John Woo has a very definite style. Watching

Blade Runner — very very definite style. The director choreographs

it. He's evoking an emotional response from the audience by the way

he moves his camera. Most of the time you're not aware of it. Sometimes

you're so aware of it that it's a pain in the neck.

But in an ideal situation, it all becomes one and just sweeps you along.

With swordplay, do you have the opportunity to teach an actor footwork before

you get into any of the swordwork?

Yes, to me it all starts with your feet. Your feet are your base.... What happens with

actors who [aren't aware of their body is that they act with just their

arms and head] and as a result, they tend to be dead from the waist

down. What it does is it cheats the audience of a more articulate story,

and it cheats the actor too.... [When you start an action from your

feet] it actually extends the moment every so slightly, and at the same

time the entire body is telling the same story. So it starts from the

feet up and is supported from the feet up.

If you're in close, you don't see this, but you do see it in the... balance of the artist.

As fight scenes get more complicated, for example on horseback, how do

you maintain the safety factor?

Well, safety is always first, as far as I'm concerned.

As soon as you start adding another element — it's tough enough taking care of yourself,

and then you bring a partner into that. Then the two of you are taking

care of each other while you train.

Even when [two actors working together] don't particularly like each other, they realize that

the work is the important thing and they focus on that....

When you bring in something like an animal like a horse, the horse is probably 900 [or]

1200 [or] 1400 pounds of unpredictability. I spent about five years

honing my horse skills for that very reason. As a result, I did a picture

in Jordan, I did a picture in South Africa... all of which involved

horses. I was very happy I had taken the time on my own because it allows

me not to just [mimics someone riding wobbly in the saddle, laughter].

I had conquered that. I had credibility.... I also had enough strength

on horseback to think of spending just a little time with the horse

to work out the same [type of] cues that Simon and I were exchanging.

Different horses are trained different ways; it doesn't really much

matter. Once the horse understands what it is you're asking him to do,

and if you do it in a gentle, suble way, you have won yourself an ally.

And you want an ally; you don't want an adversary.

But working with a horse, yes, it does open up a whole lot.... Horses aren't machines.

A lot of people don't realize that when you work with a horse, you only

have a certain amount of time.... So it's a hard job. It's difficult,

but at the same time there are few things more magnificent than seeing

two people on horseback wielding swords.

In movies you see people get run through with the sword coming out of their

back. How is that done?

They have a couple of ways. They will cheat using a shorter sword and let the other guy

fake a reaction. They also use something that's actually kind of a belt

with [the sword cutting off where it meets the body, the belt going

around the body, then the end of the sword on the other side of the

body]. Those are two very standard ways of doing it.

I think the sword has a romance and a nobility to it. It represents the idea of [fighting

your own battles], and with shows like Highlander, a sense of

responsibility and an attempt to do the right thing.

I think why Klingons [from Star Trek] are such popular characters is because where

they may seem outwardly cruel, there is an inherent nobility to their

willingness to stand up one-on-one.

I think that one of the great things about Gene Roddenberry's [creator of Star Trek]

vision of a better world, a better galaxy, was his attempt to do the

right thing — you have characters who believe in doing the right

thing. His people have a moral center, a moral character if you will,

a role model. We don't get very much of that and I really like that.

That's one of the reasons I'm very [proud] to be associated with the

Star Trek universe.

And also the Highlander universe is another situation where, I think, the heart of the story

["Duende" episode] was the sword. The sword was representative

of yes, some things are worth fighting for and I will stand up and fight

for [them].

As I said yesterday, there are only three outcomes to a swordfight — you lose, in which

case you die; you tie, in which case you probably both die; or you win.

So it's very important to be fighting for something worth fighting for.

Any memorable bloopers you can tell us?

When I was doing "Duende," the weather was just awful — it was raining

— to the point where after shooting for an hour we had to stop

because it was too dark for us to shoot. The surface we were working

on actually developed almost an inch of water, and we were fencing away,

and all of a sudden I disappeared from [the camera] frame. And it was

like someone down below frame threw water back up into the frame to

replace me. It was [so] slippery, both my feet went out from under me,

and I tossed the swords away so I wouldn't impale Adrian. And I just

suddenly disappeared. And Adrian looked at the camera . He goes, "You

see. You see. We told you this would be slippery."

And also, when I got up — he helped me up — he put his arm around me [and started

singing and dancing to] "We're singing in the rain..."

Is the workshop you teach just for professional actors?

The information is available for everybody. Everybody can learn something. What it's

really all about is body balance and movement and confidence and working

with a partner. And developing sensitivity and awareness.

One of the things I learned from [?], one of my great teachers, is when you work with

sensitivity and awareness, everyone you work with will teach you. And

everything you work with will teach you, will suddenly start to reveal

its secrets to you.

Anybody else? No? I thank you very much. I had a wonderful time.

Applause and a standing ovation — Anthony was the only guest I saw that day who got a standing

ovation. If you want to know more about Anthony, his fan club, or the

classes he teaches, visit his webpage at www.delongis.com.

| To top |